I’ve had studio visitors lately, and sometimes when that happens the flat files get opened to a collection of drawings in a variety of mediums, some that have rarely seen daylight in years. This accumulation is to the point where I now am regularly surprised to uncover pieces I’d forgotten about.

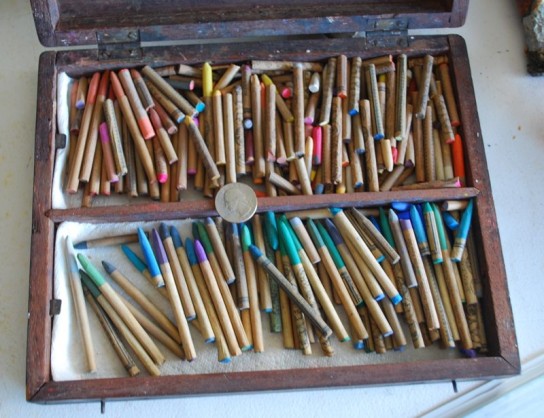

Drawing was my first love in art. I imagined just “drawing” as a profession long before painting began to come into the picture, and I return to it as often as I can in some form or another.

Often if there is an emotional upturn or downturn in my life, I’ll eventually find myself drawing somewhere. Alone with a tree, a person, or other subject, drawing centers my attention outside and away from myself. That’s a very good thing, a creative and constructive place for that sort of emotional energy, and it leaves something tangible that may be of value to others.

Tree Study Conte Crayon on paper

Tree Study Conte Crayon on paper

Trees are great subjects for learning to grasp the large shapes (something I struggle with) and for experiencing as beautiful, living forms. I draw them out of a desire for the discipline that accompanies outdoor drawing, done carefully but not with tedious detail. When one draws something with a certain degree of fidelity, it’s most certainly not “slavishly copying” but absorbing the subject, bringing it into cognition at an intuitive level. Inside one of my watercolor palettes, I have written a three word maxim: ” Suggest, don’t explain”, which applies to drawing as well as conversation. Don’t we all know the person who, when asked a question, offers far too much information in response, to the point where you’re sorry you asked? To be able to distill a paragraph into a sentence or two has so much more gravity. I think it works that way in drawing and painting.

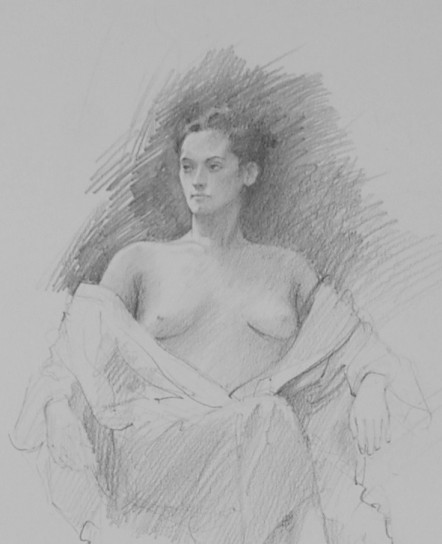

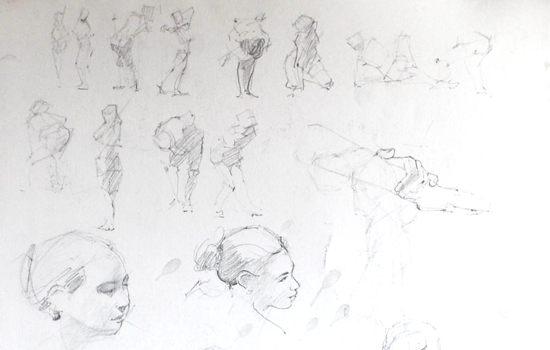

Here are some other examples I hope might be of interest, graphite pencil on Strathmore drawing paper, 11 x 14′ or so, and drawn from nature for various reasons.

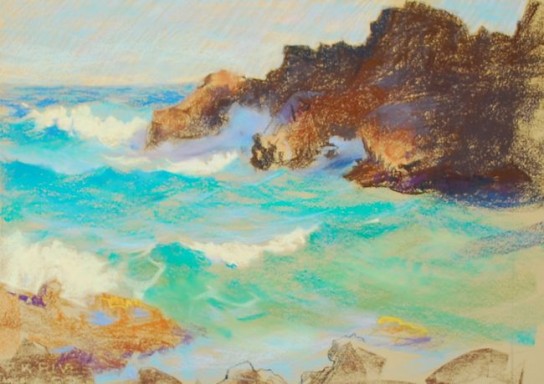

The ocean pieces are especially challenging because it’s moving, and you have to harness that somehow, make it intelligible by giving it direction. The values are pretty high, and the usual line conventions can’t tell the full story. Homer (Winslow, not Simpson) worked wave themes out in black and white on toned paper, as painters so often have.

With enough practice, you begin to anticipate certain characteristic motions in the sea, and once it gets under your skin a bit, your ability to recall it increases. I don’t know that you can develop that sense with photography. I’m reminded (and invigorated) by that great story about Frederick Waugh being able to draw a wave at any point in it’s progression convincingly out of his head, the result of the effort he put into studying them while living on the island of Sark in the English Channel.

Architectural subjects are always great to sharpen my eye, almost the opposite of the wave drawings. The visual measuring was a real difficulty, but I love this old steeple and wanted to work it out with a “loose correctness”. That required a lot of seeing past and through the details, finding the big blocks they’re covering. Just like the figure, come to think of it.

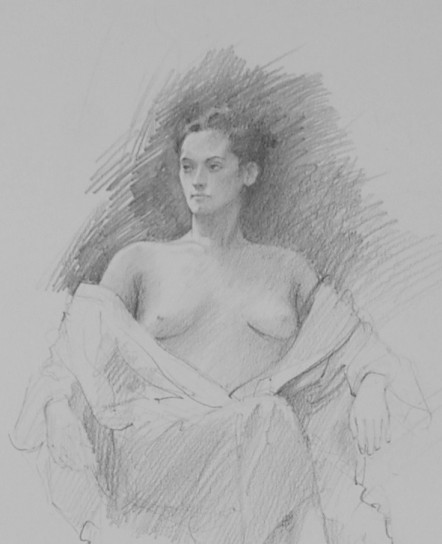

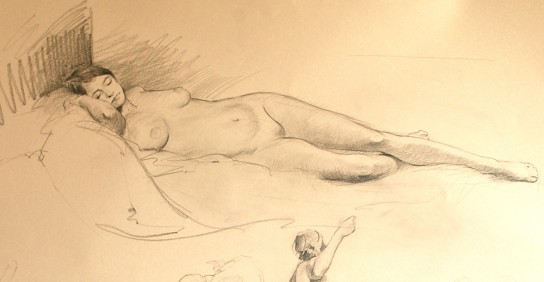

Speaking of which, here’s one of a number of the figure drawings that I work out in my figure classes, and there’s no end to what can be studied there. Just showing up, as in so many things in life, puts you on the right track, and the incremental investment over time of studying the live model is invaluable.

Last night, I was just rereading the Drawing chapter in Birge Harrisons’ classic “Landscape Painting” (1910) where he wrote the following:

“…you will find it difficult to place your finger on the name of a really fine landscape painter who is not also a fine draughtsman…inquiry will disclose the fact that the best of them have devoted at least four or five years exclusively to the study of drawing. This is none too much. But the best place to acquire this knowledge, even for the landscape painter, is not out of doors before nature; because it is so much easier to study drawing indoors from the nude.” (p.81)

So, I guess we know what we have to do. It’s endless, thankfully.

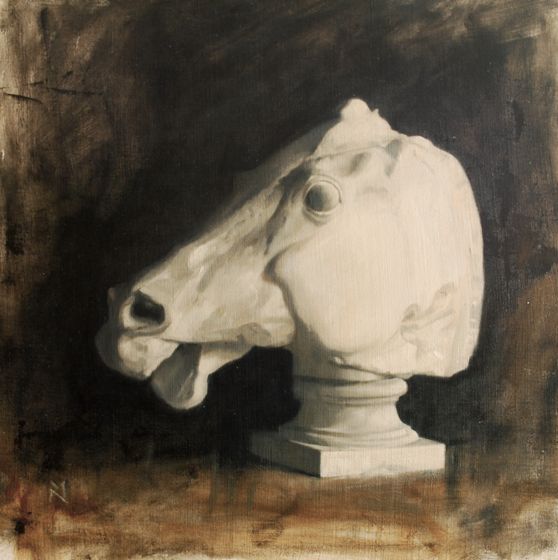

Parthenon cast, oil 22 x 24″

Parthenon cast, oil 22 x 24″ The Man

The Man

Makapu’u-Evening Sea oil on linen, 32 x 36″

Makapu’u-Evening Sea oil on linen, 32 x 36″

First sketchbook indication.

First sketchbook indication. Tree Study Conte Crayon on paper

Tree Study Conte Crayon on paper

“Kewalo Basin, the Laysan” 24 x 18″ oil on panel

“Kewalo Basin, the Laysan” 24 x 18″ oil on panel