Willard Metcalf (1858-1925) has been one of my favorite American landscape painters since I first encountered his work at the Spanierman gallery in the 1980’s. I never tire of him, and love to introduce him to modern painters who don’t know his work.

Metcalf was chiefly a painter of the New England countryside, and his works possess a spaciousness and beauty that seems to be the result of massive natural affinity for his subject, talent, and a tremendous grasp of essentials.

Here, we have the opportunity to examine one of his outdoor studies and then be able to compare it to a finished painting. Both works were painted in 1887, when the artist was twenty nine, and working at Giverny, France with the group of painters attracted to and surrounding Claude Monet. What a time that must have been!

My often repeated (to myself, anyway) statements about the value of seeing “unfinished” works by great painters holds true here. It’s like a backstage pass to a magic show, where the hidden apparatus of how things are done is more easily discerned than from the audience side.

In this study or sketch ( I think of it as more than a sketch) all the basics of the location and the movement of the eye in the composition are evident, but are painted pretty bare-bones, everything being reduced to values and rough hewn shapes.

Giverny, oil on canvas, 12 x 16″

After the initial attraction of the foreground shadow leading to the tree and the shaded area left of it, the dark passage attracts us to the right side of the canvas. This strategic element has a great effect on the balance of the picture, both by contrast (it’s the darkest spot directly next to a light) by weight (it’s close to the edge), and line (the shape of the river). Without that dark, I don’t think the eye would have much incentive to do anything but zoom right out on the upper left hand corner and be gone. But because of it, we cross the canvas to see what’s going on, and then walk our way back across the picture to the exit provided by the interest of the buildings and patch of sky. You can test this easily by covering the dark patch with your thumb and observing what your eye does.

The answer to the question of how Metcalf decided on such things and makes them operate without us even noticing is that it’s all planned. The initial thinking for this painting had to include where the eye would be led. An enormous part of the pleasure in experiencing his works is this marvelous business of composing carefully.

Giverny , oil on canvas, 26 x 32″

Giverny , oil on canvas, 26 x 32″

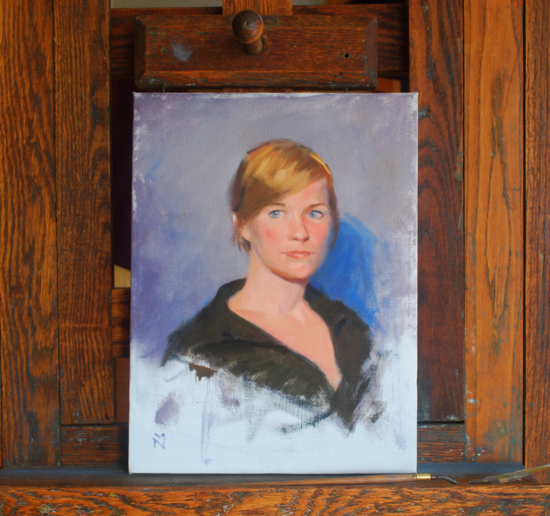

And here, we see what he eventually arrived at in his finished painting. I have no way of saying for sure that this was painted directly from nature or was a studio work from the study above, which is, by the way, about one quarter size of the final painting. It could easily be both, and that’s my guess. But the question I have is this: would he have possibly arrived at the beautiful completed work without the initial study effort? We can see that his generation of well-trained artists moved slowly and thoughtfully, and that their work reflects this.

The continuing lesson is about planning our work carefully, slowing down, equipping ourselves with experience and knowledge of composition, and giving ourselves the best possible chance of a worthwhile outcome for our efforts.

Today, so many painters of the landscape seem burdened by the belief that a painting increases in artistic merit by being completed in one session. The evidence of the late nineteenth century indicates quite the opposite, does it not? I suspect that current practice is more a function of our culture, pushed by inner restlessness, and I believe that this confusion of a sort of alla prima painting with plein air painting needs a second look. I don’t believe I’m qualified for the job, and can think of many who are, but since they are quiet maybe I’ll attempt that another time anyway.

Giverny , oil on canvas, 26 x 32″

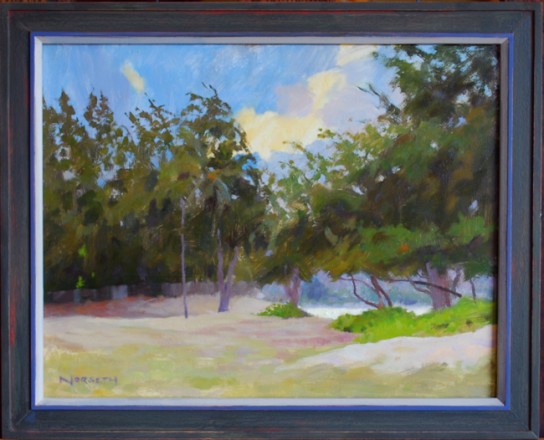

Giverny , oil on canvas, 26 x 32″ Silver -Grey, a Corner of Kailua Oil on Linen 20 x 22″

Silver -Grey, a Corner of Kailua Oil on Linen 20 x 22″ Halona Cove, final painting, watercolor, 15 x 22″

Halona Cove, final painting, watercolor, 15 x 22″ Halona Cove watercolor study, 11 x 14″

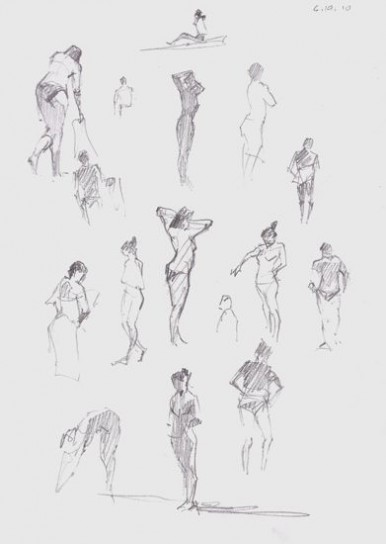

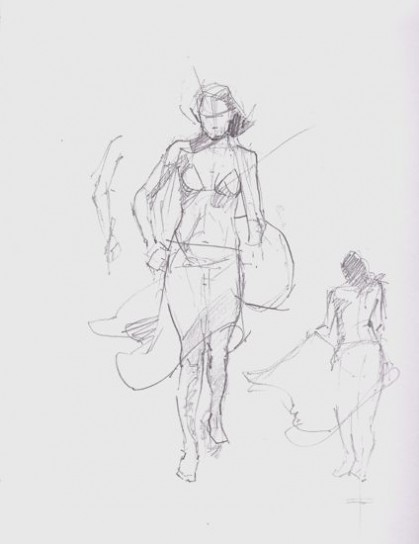

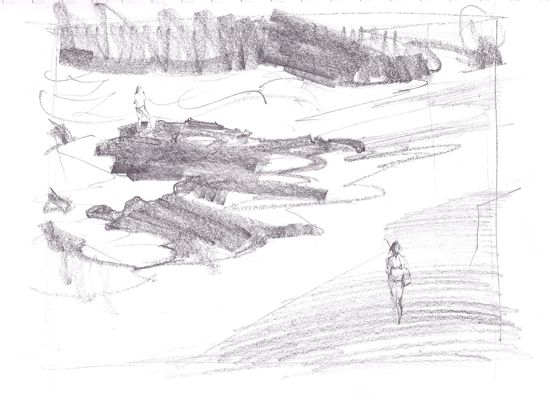

Halona Cove watercolor study, 11 x 14″ I find that compositional sketches, a simple breaking down of the basic elements into patterns, is indispensable.

I find that compositional sketches, a simple breaking down of the basic elements into patterns, is indispensable.