So…where does your eye go?

That’s a question I’ve loved asking people as we view artwork together.

I love it because it begins to open us up to the idea that there may be a deeper experience awaiting when looking at a painting. That without any awareness on our part, a piece we’re viewing may be subtly guiding our eye intentionally.

An interesting side of composition involves the deliberate leading of the viewer’s eye. It’s not something I was every really “taught”, but since realizing that it exists, it’s added a lot to my enjoyment of good paintings and drawings.

I think it’ll do the same for you. But the first step is to study what attracts our attention and what gets it to move in a picture.

A Power of Attraction

Our eye is always searching…in a sense, it’s hungry. We can notice how it works when leafing through the pages of a book, searches a room for misplaced keys, or recognizes a familiar person in a crowded public space. Our attention is drawn and engaged before we know it. For our purposes now, we’ll simply call a this a “power of attraction”.

For paintings a “power of attraction” is anything within a picture’s composition that can attract your eye. We already know that a bright color in a drab setting or a human figure in a landscape can become a center of attention…what a lot of people call a “focal point”.But let’s consider what else an artist might use to move your attention in a more subtle way. Just for starters it could be any of the following…

-an open window or doorway in a background

-a contrast of light or dark, such as a highlight on a dark shape

-a color, by it’s strength or by contrast

-a contrast of objects…something that differs from others within it’s setting

-a figure or animal

-a sharp edge surrounded by softer edges

-any point/mark that has “power” due to it’s placement, especially nearer to an edge of the painting

Whatever it might be, it will possess a visual magnetism that makes itself known to you subconsciously. And importantly, not all objects have equal power of attraction.

As I gradually became used to this, it became very interesting to look at a picture merely only to see how the artist would draw my attention from one point to another. One specific moment I learned a strange truth…that the central and dominant THING in a painting was not the main subject but an essentially abstract shape placed in the full light, with the artist in the self-portrait playing a slightly secondary role. I found that reasoning to be fascinating.

And the artist?

Rembrandt Van Rijn

Why Study Rembrandt?

Though there are countless examples in traditional art we can study, I found that Rembrandt, and especially his drawings, are the ideal place to begin seeing this business in action. Often his seemingly modest & commonplace themes become excellent lessons in leading the eye.

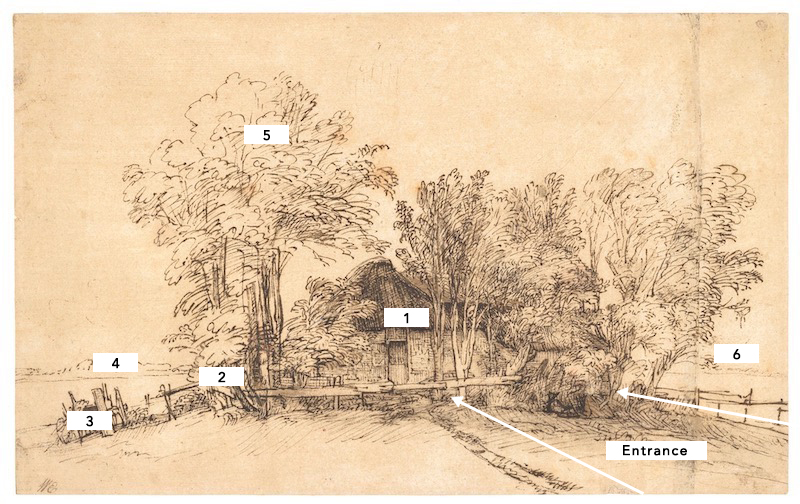

As an introduction to the concept for us to try together, this pen drawing is a fine example. I recommend that you enjoy a few moments with it before proceeding. Just pause and ask yourself where your eye wants to go as you examine it.

Rembrandt’s pen and ink drawings have a variety of “attraction” points that reveal themselves with a bit of looking. The drawings were often created on ramblings in his town and surrounding countryside. This was not an extraordinary sight in Rembrandt’s day, perhaps the same as an everyday home would appear in our own neighborhood. These drawings represent his everyday experience, just as we also have our own familiar features of our time. He was an eager observer, and exercised his gifts of observation and interpretation continually.

In this example, you may have noticed that your eye moved from part to part, resting here and there, and connecting one spot in the drawing to another.

A focal point isn’t enough

Having a point of interest that dominates the picture (a focal point) isn’t really the same as creating a series of connections that can lead a viewer through a picture. The reason is because a single focal point’s value is mostly only interesting as an object. The alternative we see with the Rembrandt drawing, a designed picture suggesting a discernible pathway, is a series of small discoveries that gives our mind an incentive to engage. Ideally, one is led to travel through the picture rather than looking at the picture.

Below is a breakdown of what I get from my own study of this beautiful drawing. I’ve found that the various things that attract my eye have differing strengths, but that with one thought a pattern can arise. But that’s just my interpretation. Where does YOUR eye lead you?

While I admit my diagram is subjective, I hope you agree that this is a dimension of picture enjoyment that, for an artist, is a valuable way to unify a composition. Rembrandt’s drawn works (for me) are a particularly enjoyable source for seeing this in action. If you’d like to dig deeper, I suggest looking at the library for books on Rembrandt’s drawings, or finding the old Dover publications of “Drawings of Rembrandt” (volume II is my favorite) as a starter.

If you want to really get a handle on composition, it’s a fascinating dimension.