As we wade into this topic, you should know that I love Rembrandt’s drawings and look at them often…for both pleasure and for learning purposes. You should also know that I’m not a Rembrandt scholar. I’m simply an artist eager to look at Rembrandt drawings to learn about composition…and whatever else great painters such as Rembrandt might have used to put their pictures together.

The Miracle on the Water

The drawing we’re looking at here is one of many Rembrandt drew around New Testament Biblical accounts. In this case, the telling of Christ’s miracle of walking on the water, and specifically the Gospel of Matthew account, which is the only one to mention Peter’s attempt to walk on the water himself. For those interested or unfamiliar, you can read the biblical accounts here.

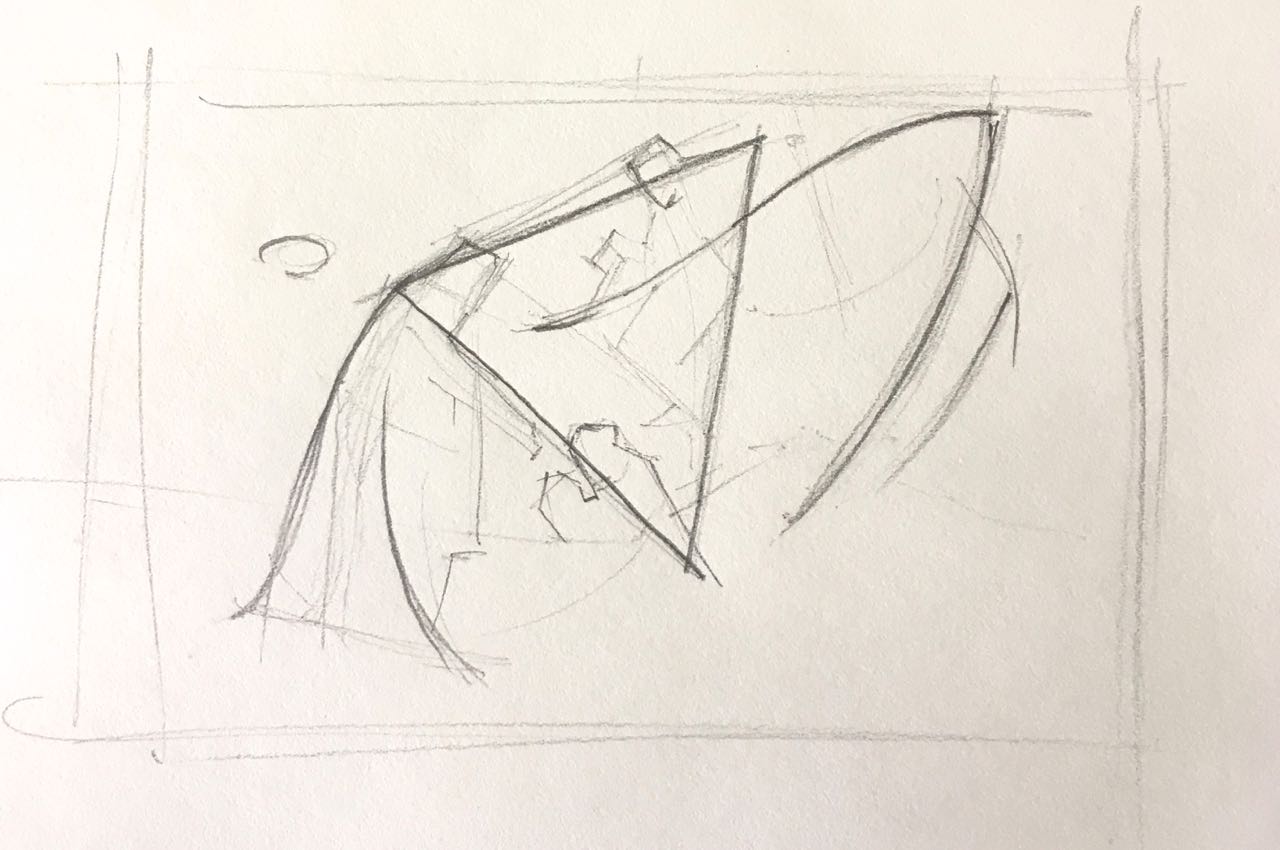

Rembrandt’s purpose in making the drawing was likely to work out how he might present the story visually in a painting. Whether he intended this drawing to be viewed by the public or drew it as a private expedition, I can’t say…the scholars might know. But either way, it’s likely a compositional drawing…concerned with deciding on the viewer’s (that’s us) point of view, choosing the characters involved, and pinning down the precise point of action to be depicted.

It’s such a curious drawing… delicate and refined in some portions and heavier in line and rougher in effect in others. Compare the refinement of the figures of Christ and Peter to the boxier character climbing out of the boat. You can easily imagine that his legs, simply drawn, are an afterthought and his figure originally ended at the railing of the boat as his smaller companions does. That difference contributes to my idea that it was a working sketch, with choices and changes evolving along the way.

An organized sketch

Though sketch like, the drawing is a clearly organized arrangement. You can always look to Rembrandt for wonderful lessons in organization and leading the eye. There’s a sweep from Christ’s figure on the left to the boat’s hull and back, which provides a sort of rocking feeling that is appropriate to the conditions of the sea. But I also find that after we step inside the drawing, there’s a particular path our attention wants to follow. As with many Rembrandt drawings, this is arranged deliberately.

Here’s a diagram of the triangular relationship that’s at the heart of the drawing. Thoughtfully considered, one will notice a sequential arrangement of not only the actions but the intentions of the characters involved.

Triangular relationship of key actions

As the Gospel story indicates, only Peter asked the he might leave the boat. So what is interesting is how the characters are illustrating, and I’d say animating, an entire sequence of action.

A sequential animation?

Due to placement, Christ’s figure attracts our attention from the start, and we easily follow His arm to poor, foundering Peter, angled so powerfully in Jesus’ direction. From there, our attention most easily moves up and to the third corner of the triangle with the boldly drawn (and unidentifiable) character just leaving the boat. Look at that figure’s elbow forming the right corner of our triangle. Does he even seem aware of what’s going on beneath him? And to the left of him, we see the young-looking fellow tucked away behind. He’s only observing…but an important element, bridging the space from the boat over to the head of Christ reaching down to rescue Peter, their hands almost, but just not quite, touching (a wonderful choice). And the animation repeats itself…a cycle of questioning, deciding, acting, failing, and finally rescuing. A profound statement of the faith process.

A subtle, interesting light source

Another surprising feature of this drawing started with my questioning the indications of light and shade in the drawing. Often Rembrandt’s more complete drawings utilized tones of wash to indicate light and shade, but not in this case. This is a line drawing only; though somewhat rough in the application, there are (what artist’s call) cast shadows on the hull of the boat, and correspondingly on the ocean. A cast shadow occurs when an object, in this instance the boat, is completely blocking the light source…(the darker the shadow, the brighter the light) and the figure of Christ and of Peter are very carefully shaded with even hatching lines, exactly as if backlit. I wondered about the intention of this, but the reason gradually became clear. The oval behind Christ is a representation of the moon, and we then remember (from the biblical account) that this drawing represents a nighttime event.

I invite you to try and view the drawing in that sense…do you agree that the drawing becomes a much richer experience? Hopefully you can imagine and admire the thinking and visualization necessary to put this together, and yet we should not be surprised. Rembrandt’s drawings are like that.

I’d love to hear your comments and thoughts!

(And, as sometimes is the case, there’s been recent suspicion that the drawing is not by Rembrandt! You can find British Museum information concerning that here).

If you’d like to read my post of another Rembrandt analysis, it’s found here.