Responding to a surprising improvement

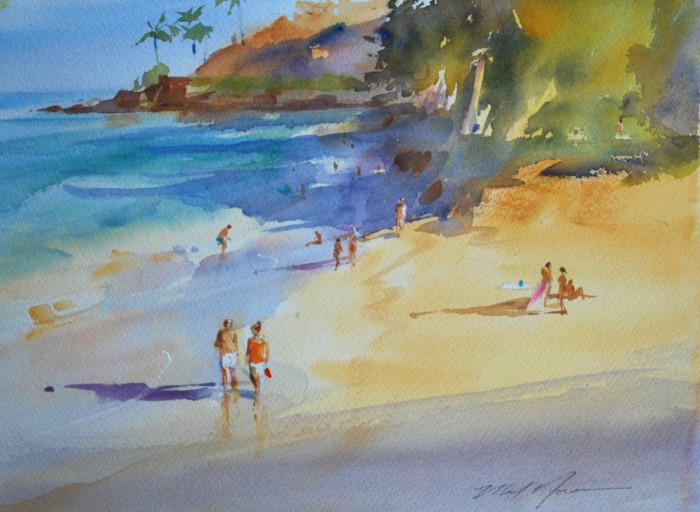

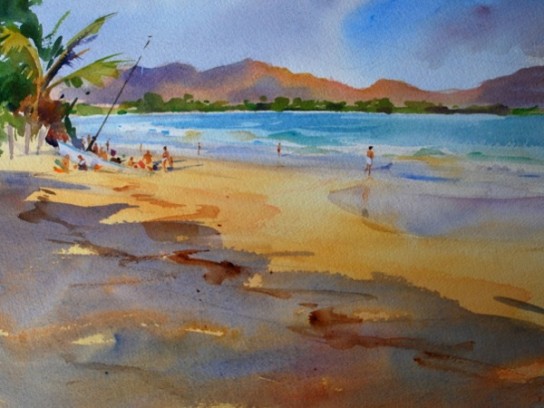

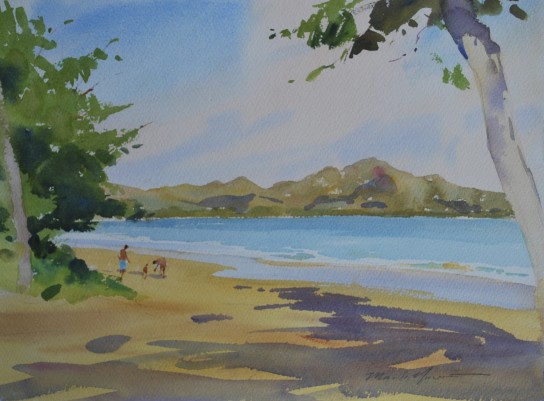

While working outdoors on a watercolor, I ran into a situation…a scene before me greatly improved as I was working by the unexpected addition of a pair of figures that were not part of the original concept.

Since I’d already begun applying paint to the piece, these characters couldn’t simply be added into the composition. But I knew their addition would make such a vast improvement that I couldn’t just let the opportunity pass me by. I decided to make a completely new painting, but I knew that there would be no time to do so directly and at the location.

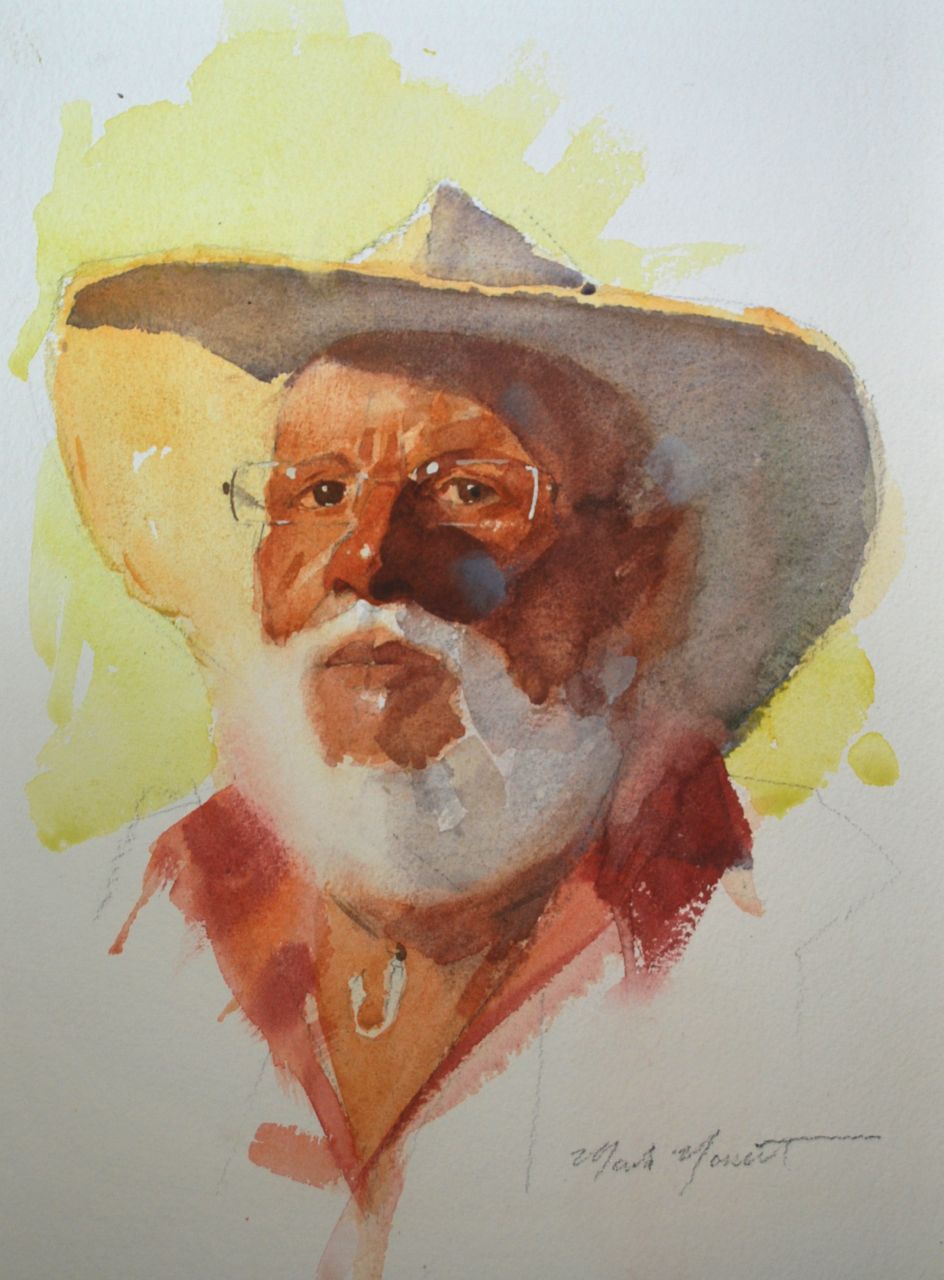

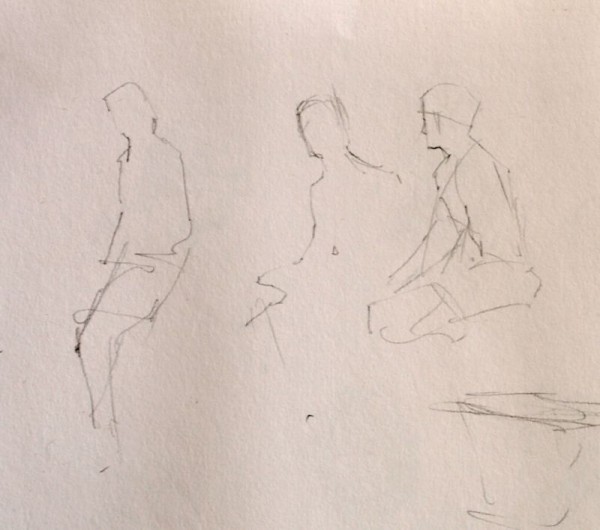

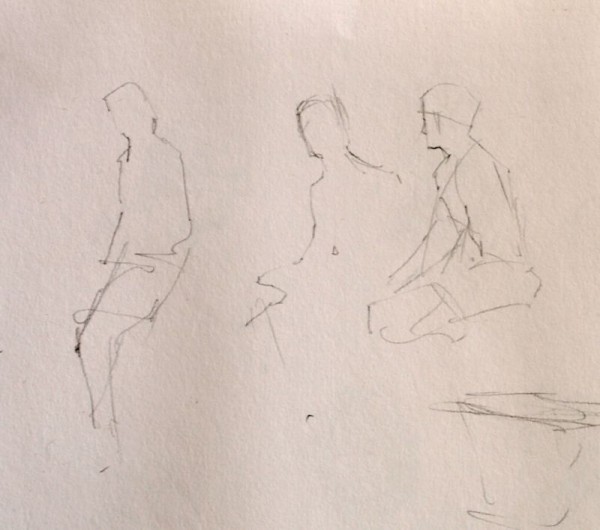

So, my first step was to sketch these two figures hastily in my sketchbook. These guys, who happened by and were now sitting only yards away, weren’t likely to cheerfully respond to a request that they pose for me, so I dashed them off rather secretly…their silhouette and relative position to the horizon…so I could place them into a new composition and have them be the correct size. I then made some mental notes, watching how they interacted, their posture, gestures, and so forth.

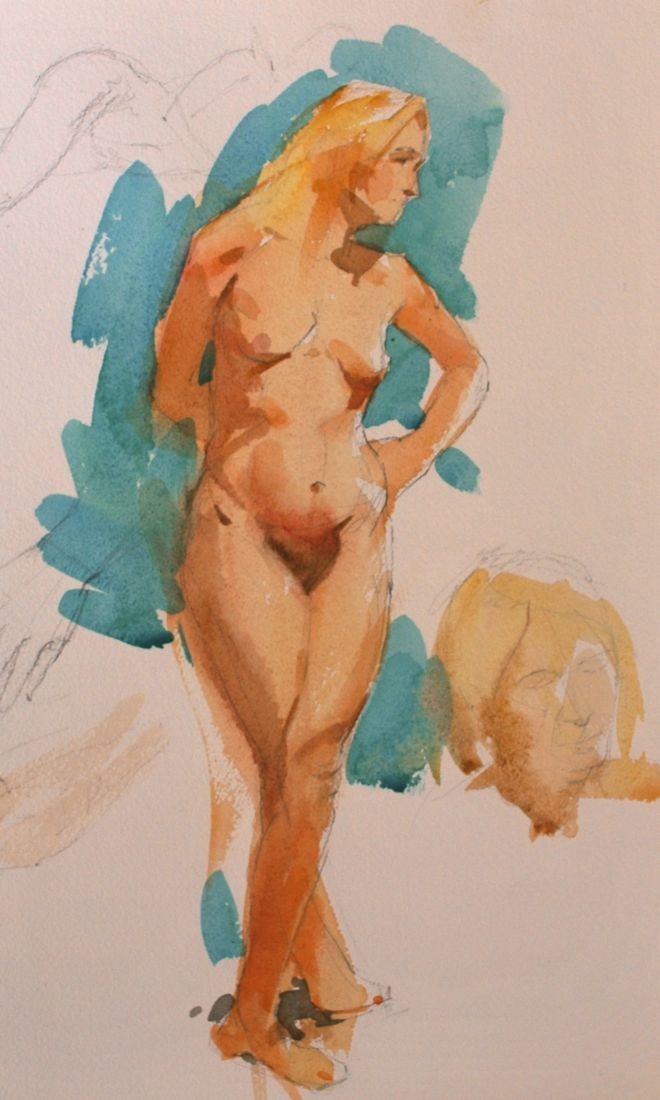

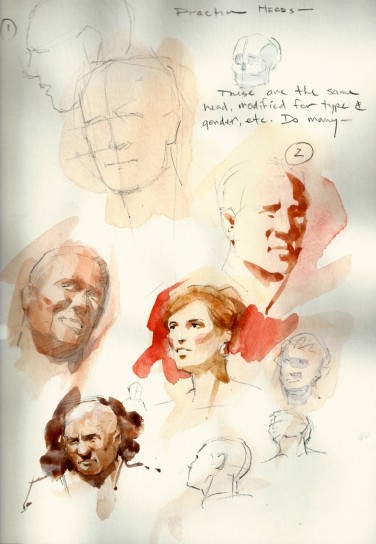

The sketchbook drawings

The sketchbook drawings

This accomplished, I was free to leave the location with a plan to start a new painting in my studio the next day, relying on my incomplete painting, the new figures in the sketchbook, and hopefully some luck.

A Studio solution to a Plein Air problem

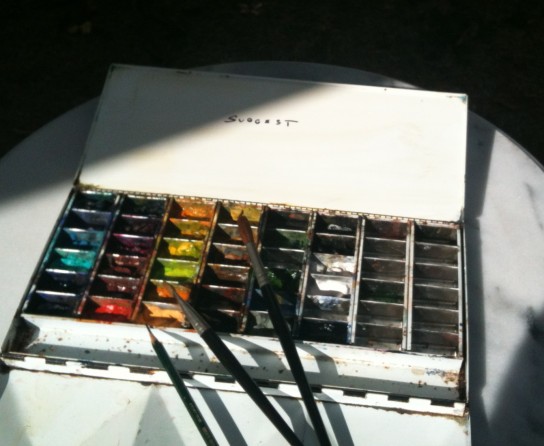

I have a background that includes having worked as an illustrator. Illustrators are pragmatic artist/craftsmen and accustomed to solving problems efficiently. They’ve developed a large playbook of applied techniques and one of the great tools of the trade is the use of tracing paper for refining and transferring drawings.

To shape the quick sketchbook notations into viable figures that would hold up in my painting, I would need to refine them from memory and a certain amount of invention. That’s where tracing paper came in….I created overlays of the rough drawings, gradually adding details from memory, refining and retracing until I had two figures of the correct size that expressed what I was after in the painting. Because I did so on tracing paper, that stage of work was all done without touching the delicate watercolor surface, which does not enjoy erasure and revision.

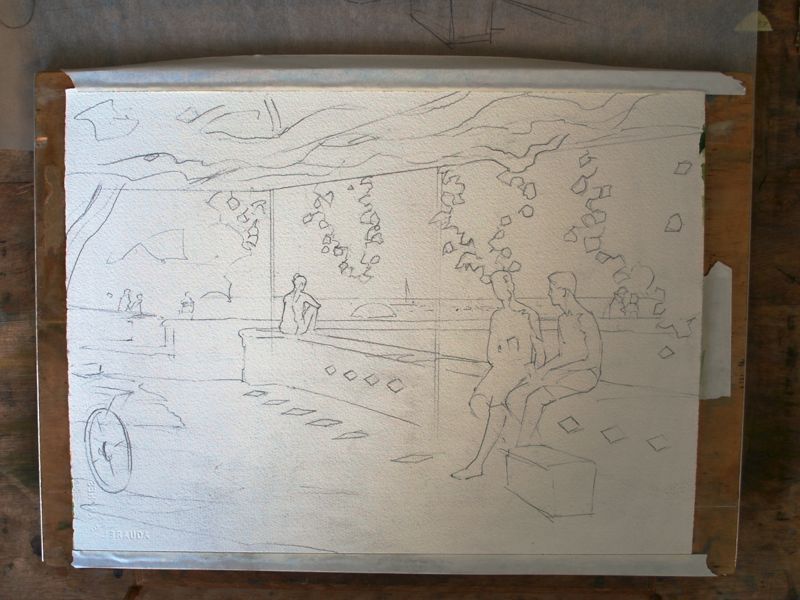

After a couple hours work, the elements of the entire composition were combined on tracing paper and were ready to be transferred to the quarter sheet of watercolor paper for painting.

For this I used a simple graphite transfer sheet(above) that one can easily make themselves with graphite, a piece of tracing paper, and perhaps a bit of rubbing alcohol to liquify the graphite on the transfer sheet. I placed my graphite transfer sheet (graphite side down) between the securely positioned tracing paper drawing and the watercolor paper, and traced with a ballpoint pen over the original drawing.

The tracing paper cartoon positioned over the watercolor sheet. The transfer has already been accomplished, and is visible beneath the tracing paper, which has been moved aside slightly to reveal the transfer.

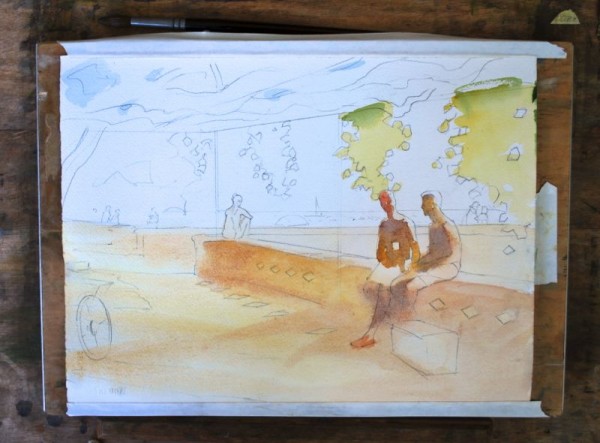

The next step was to fold back the tracing paper and strengthen the graphite transfer with the usual pencil work. One can flip the cartoon back into position if anything hasn’t transferred.

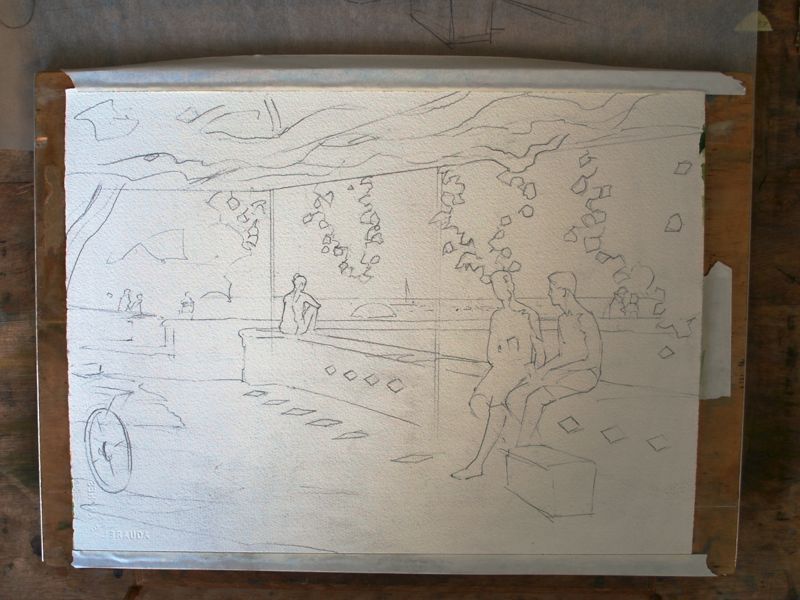

The transfer on watercolor paper, strengthened with my customary pencil work

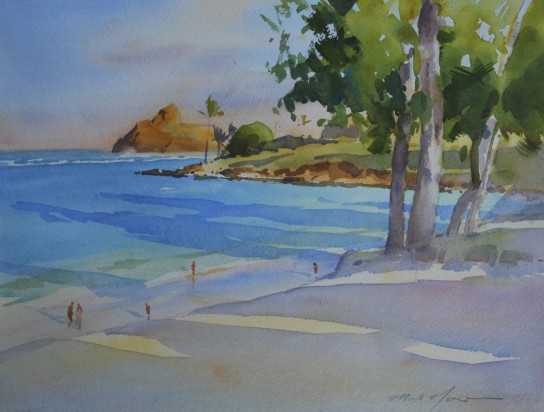

At this point I have a pristine sheet of watercolor paper with the drawing positioned exactly as needed, with all of the figures worked out adequately, and without any erasure damage to the watercolor paper.

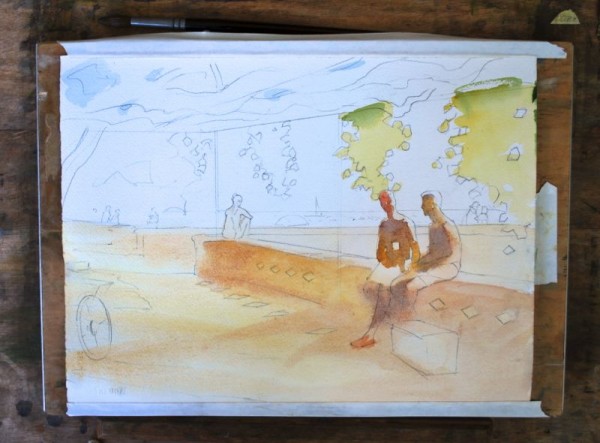

I then resumed my normal painting sequence, beginning with the figures because of their difficulty, and moving outward and around from there. I’m referring to the prior painting from the location for color and some details.

And on it went!